"We know that no one ever seizes power with the intention of relinquishing it."

-1984

You know that you're in the 21st Century when an internet corporation declares war on a country.

http://roomfordebate.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/01/15/can-google-beat-china/

When Google made the announcement that it would shut down it's Chinese search engine due to government censorship, the world was shocked by the news. While China's disregard for human rights had been made very apparent over the last few years, this was by far the largest reaction towards that rational yet: Google was actually shutting down it's search engine there as a protest against China's oppressive society.

The reason the Chinese government censors it's web is the same reason for it's state run media: the government of China since the communist takeover spearheaded by Mao Zedong has been very oppressive for the sake of destroying all possible resistance or threats to power. In a way, China's government somewhat resembles INGSOC from 1984, in that they seek to control their populace mostly for the sake of keeping the communists in power. There have been many small rebellions by the people, but they have not ended well. We all remember what happened in Tienanmen Square in the 1908's.

China is especially censoring of media that comes from out of state. Only 2 or 3 foreign films are allowed to be shown per year in the country. With the internet connection people around the world China has upped the ante, with the government creating filters that censor websites. Some of the most prominent examples were the censoring of Google, and the outright blocking of YouTube.

Despite the outrageous polices of China in terms of the internet, some have actually praised those methods as an alternative for fighting piracy. As discussed before, the advent of the internet allows the Long Tail to be exploited, and there are many materials to be offered, sometimes through piracy. Some have said that imposing a firewall similar to China would possibly help curtail piracy.

In reality it would be counter-effective. China's firewall is very easy to pass via a proxy server or other workaround, and while a US firewall may be more technologically competent there would inevitably be workarounds and backdoors. Also the firewall has been received negatively by the Chinese, and as Americans can be more vocal in protests, an American firewall would just cause more problems in meatspace and cyberspace than solve.

But Google is not the only example of technology being used to protest government. In 2009, there was a massive outcry in Iran against the election results, and students took to the streets expressing their anger. While Iran's government is oppressive for religious reasons as opposed to political, it remains similar to China. Protesters conducted Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attacks against government websites, and exchanged methods for this via social networking sites like Facebook. In response, Iran shut off internet access completely.

The protesters didn't stop there though. They used the Twitter messaging service to co-ordinate protests and DDoS attacks, as well as receruit hackers. The Iranian government's response was twofold: first they looked for Twitter accounts to see who had their location set to the capital city, Tehran, so they could track the user of that phone and arrest them. Word of the protests had spread though, and before long many people around the world set their location to Tehran to fool the Iranian government. Iran eventually blocked the usage of cell phones all together.

1984 never discussed how something akin to the internet could be used to bring down a government, although novels of the "cyberpunk" genre often employ that as a plot device. The world we live in though is rapidly turning into a technologically oriented society, and the internet is now a much more powerful weapon in terms of dictating the rule of government. The internet can express the opinions of all in a free, democratic society like ours, and at the same time it can threaten to topple oppressive ones like China and Iran. This is the reason for the censorship in those nations, and now with Google declaring open dissatisfaction with China, this could be a signal that yet another uprising is about to begin.

下來與哥哥!

مرگ بر برادر بزرگ!

DOWN WITH BIG BROTHER!

Interesting links:

http://www.webcitation.org/5ic0PcGvi article on the use of Twitter in the Iranian protests.

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/06/14/world/middleeast/14iran.html?_r=1 NYT article on the protests.

Sunday, January 31, 2010

Monday, January 25, 2010

The astonishing tale of the Long Tail

There is one false aspect of marketing that refuses to go away: the idea that marketing is a popularity contest.

Let's face it, there is a load of electronic media that is released every month, but out of all that, only the best of the best we notice. The top selling songs on iTunes, the blockbusters, the critically acclaimed and/or controversial video games, all of these seem to encompass all of the media, and its because these get the most exposure due to their success. This is especially true in Hollywood, I mean if you looked at the Box Office totals as of this post, you'd think that James Cameron's sci-fi epic Avatar was the only movie playing!

But what about everything else? What happens to all of the movies, music, books, or games that don't break records for weekend grosses or number of copies sold on launch? I'm not just talking about those that may interest some but are seen as spectacular failures, I'm referring to those products, and those who manage to get moderate success but fades into obscruity, hidden in the shadow of the enormous moneymaking machines like Avatar or Modern Warfare 2 or Harry Potter or Twilight.

We are taught to follow the 80-20 rule, which in it's basic form states that out of everything sold, on 20% will sell well, and be classified as "hits." The other 80%, or "misses" are found in an untapped gold mine called the "Long Tail."

This image here is a visual illustration of the Long Tail in terms of popularity ranking. As you can see, on the left, in the green, you have your best selling products that dominate your store shelves. These are your Halo's, your Barbie's, your GI Joe's, your Tickle-Me-Elmo's and so on. The yellow on the right are the less popular products that don't sell as well as the dominant ones, and thus aren't as likely to receive store space. These are your "Bollywood" films, your Documentaries, your "Indie" albums and so on.

This image here is a visual illustration of the Long Tail in terms of popularity ranking. As you can see, on the left, in the green, you have your best selling products that dominate your store shelves. These are your Halo's, your Barbie's, your GI Joe's, your Tickle-Me-Elmo's and so on. The yellow on the right are the less popular products that don't sell as well as the dominant ones, and thus aren't as likely to receive store space. These are your "Bollywood" films, your Documentaries, your "Indie" albums and so on.One of the reasons why the Long Tail exists is due to physical space in retail stores. Stores like Wal-Mart, Meijer, and Target can only carry so many products in their inventory, and it's in the store's interest if the products they sell are guaranteed to bring them profit. To that end many retailers have various "rules" that determine which products can be sold on their shelves, for example: a CD must sell "x" amount of copies in "x" months to keep it's spot, the same applies for video games or movies or books.

Have you heard of a guy named Joel Rohweder? How about a rock band named Anvil? If you answered "no" to either, then you're not alone. Joel is a friend of mine, he's about to finish High School, and he's an aspiring musician. Anvil is a heavy metal band that made a big impact when they debuted in the 80's, and influenced many bands such as Metallica and Guns and Roses, but they were forgotten as time went on due to bad record deals. Both Joel and Anvil produce some great music, but if Kmart had to pick between them and say Led Zeppelin, they would pick Led Zeppelin because they are much more successful and have a wider audience.

It's not just music either, movies are another good example of physical scarcity and the long tail effect. This past summer, I had a chance to watch a movie called "Roadside Romeo" a Bollywood animated feature akin to a Disney Pixar movie, and it features the best of the best of Bollywood, with names like Saif Ali Khan, Kareena Kapoor, and Yash Chopra. The movie, telling about a Dog who tries to make it on the streets of Mumbai, is actually quite enjoyable, and it was received very well in India. In the US of A however, despite a distribution by Disney, the movie was only shown on 40 screens, and has not been released on DVD. The target market was simply too small, the Hindi language confusing (even though it is subtitled in English), and the "famous" stars of Bollywood are nobody to us.

However in the 1990's, something amazing happened: the internet. Now that the world was united, people began to see the potential of using this new tool to buy and sell products from stores that would have infinite space, like Amazon or eBay, or iTunes. The Long Tail was finally being brought into the spotlight.

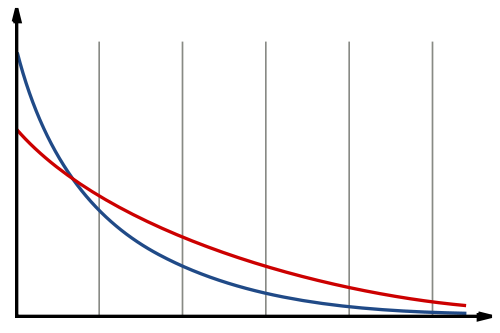

This graph shows the emergence of the Long Tail with the advent of digital distribution. Traditional retailers in the real world (aka "meatspace") are shown in blue, and they get more sales by sticking to products that are known and sell well, as seen on the left. Stores in cyberspace are shown in the red, and while they may not sell as well as their real-world counterparts, their sales increase as they go down the Long Tail and offer products that are obscure, but have a market. In cyberspace it doesn't matter how much of a market share a product can have, because it's not taking up any physical space, it's sitting harmlessly on a server in cyberspace. As long as there is someone willing to download it, then it's worth something.

This graph shows the emergence of the Long Tail with the advent of digital distribution. Traditional retailers in the real world (aka "meatspace") are shown in blue, and they get more sales by sticking to products that are known and sell well, as seen on the left. Stores in cyberspace are shown in the red, and while they may not sell as well as their real-world counterparts, their sales increase as they go down the Long Tail and offer products that are obscure, but have a market. In cyberspace it doesn't matter how much of a market share a product can have, because it's not taking up any physical space, it's sitting harmlessly on a server in cyberspace. As long as there is someone willing to download it, then it's worth something.The reason why it's taken time for online distribution to really take off is simple: piracy. Piracy was a one of the reasons why DVD's had outrageously high prices when first introduced, as the studios were concerned that illegal copies would be made and distributed. P2P networks like Morpheus, Kazza, Limewire, BearShare, eMule, BitTorrent, and so on are still in use today, but when downloading something illegally, there is a price. You may be getting it for free, but it will probably take longer to download as you will not have a dedicated server to get your file from. The quality of the media is also questionable, and of course there's the risk of contracting one of those annoying viruses, which would spoil your day fast.

Anyone who works for Apple cannot deny that the company's greatest (and in my opinion only) success's were the iPod and iTunes. The iPod has the advantage of a stable OS and being the best Music player out there in terms of functionality and reliability. But the iPod is nothing without content, and with it's impossibly large disk space, people were able to listen to pretty much all of their downloaded music.

iTunes took it a step further by selling songs at the price of 99 cents. Aside from the psychological effect of selling a product for less than a dollar, even if it's just one cent, Apple fixed the price at 99 cents so that it took the price factor out of the hands of the record labels. Now literally billions of songs are available to everyone and at a reasonable price. Not only that, but all profits go directly to the artist. Remember Joel? He's sold 5 songs now on iTunes, and all profits gained from them go to him. How about Anvil? Their new album is now available there, and like Joel, they take all the spoils, not the labels.

Netflix took iTunes' example and applied it to movies. One of the reasons video rentals even came into existence was due to the convenience, and cheapness, of renting compared to actually buying. Movies however still suffered the same restrictions as CD's, and if it didn't sell well, or was too obscure, it wouldn't be on the shelves. Netflix however has a wide variety of movies, and makes good use of the Long Tail. Documentaries for example don't have a big an audience as action movies, but there are people that still want to watch them. Now they can go on Netflix, find a documentary, and have it delivered to their home, or streamed to their PC.

In 1998, Valve Corporation released Half Life, a First Person Shooter that went on to be one of the most critically acclaimed and best selling games of the decade. In 2004, with the launch of Half Life 2 on the horizon, Valve realized they needed an alternative to retail. To that end, they created Steam, a content delivery service that allows you to purchase and download games to your PC directly. Steam has revolutionized digital distribution, because not only can you download games, but you can have a copy of those games on every PC you own, you can download games before they're released, and if there's a patch to fix some bugs in the game, Steam will automatically download the files and install them. Since 2004 all of my PC game purchases have been via Steam, and while it's not exactly an example of using the Long Tail, it's certainly a benchmark in digital distribution.

The Kindle from Amazon has done for Books what iTunes has done for music, Netflix for movies, and Steam for games. With the advent of ebooks, electronic readers are coming into play. The Kindle lets you download books from Amazon.com, as well as Newspapers and Magazines, and you can carry them on your Kindle wherever you go. This saves phyiscal space on both store shelves, and your own. Several of my books for this semester are on Kindle, and it's a relief that I don't have to carry as many books around as I used too!

Digital distribution is obviously the future of media as we know it, and with it the Long Tail is finally being tapped. Obscure artists are being given a chance to be known, and we are no longer subjected to physical shelf limitations or outrageous store prices. Now sure this means that in a few years there will be considerably smaller Wal Marts, and the record labels are essentially dinosaurs now, but sometimes change can be good, and with the Long Tail and digital distribution opening up new doors for us all, I'm certain that this is, as someone once said in a different context, "change we can believe in."

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)